Nearly eight years after my father’s death, I received a phone call from the nurse I had hired at the end of his life. Jen was a kind and compassionate person, and she had been at his side when he passed away. Because of her other commitments, she was unable to attend his funeral, but she posted a condolence note to his obituary notice on Legacy.com.

When her voicemail appeared unannounced on my phone, I assumed she wanted a reference. But it was nothing of the sort. When I called her back, she told me that she had received a manila envelope in the mail containing an unsigned document that denounced my father. “Why would anyone do that to someone who is dead?” she wondered aloud.

It troubled her that the sender of the document found her address since she had moved three times since my father died. She said she had almost decided not to call me. But then she changed her mind. “It’s probably some rival lawyer or judge who was jealous of him,” she guessed.

I doubted it. By the time my father died, most of his contemporaries had passed on, and the generation of lawyers who had argued cases in his courtroom were retiring. In his day, the judges liked to play practical jokes on each other. Once my father drove around for months without noticing a bumper sticker on his car that said, “Party Naked.” But that was as far as it went. My father did not make professional enemies. One would have to hate another person to attack him so many years after his death.

“Did the person who wrote the letter threaten you?” I asked.

“No,” replied Jen.

“Then I don’t think the police will be interested. Where was it postmarked from?”

“Greenwich, Connecticut.”

I had an inkling, and part of me did not want to hear anymore. For a moment I wrestled with myself, and then I said, “Why don’t you take pictures of it with your phone, and then text them to me?”

About ten minutes later I got her text. There were fourteen pages, but I did not have to read very far for my suspicions to be confirmed. I checked the obituary on Legacy.com that I had posted for my father after he died and noted the names of those who had left comments. I called Jen back.

“Hi Jen,” I said. “I had a feeling about who sent this, and I was right. You may remember that my father was a man with four daughters”

“I do.”

“We also have a brother. He’s been estranged from the rest of us for many years. My parents had nothing to do with him, and I don’t either. He’s the one who wrote this. I know that at one time he was living in Westchester. That’s not far from Greenwich.” I flipped through the pages that I’d uploaded on my computer. “You see here he identifies himself. He refers to himself as ‘the male offspring.’”

“I didn’t read it all,” she admitted.

“The person who wrote this, whom I believe to be my brother, is insisting that everyone who wrote comments on Legacy.com make a public retraction because my father was a terrible person. Some of the people who left comments are acquaintances. One is the son of one of our doctors. Some of them didn’t even know my father. They are friends of mine or my sisters.”

“Oh, that’s what it is,” Jen said. She sounded noticeably relieved. “Well, every family has someone like that.”

I wondered if she was right. “No one would do what he demands. It’s crazy. I wouldn’t worry about it if I were you,” I assured her.

I took the opportunity to chat with Jen for a little while. She confessed to the difficulties of working as a nurse in a hospital in Birmingham, Alabama, during the pandemic. “People don’t care,” she said. “I take every precaution, and they just don’t care.”

I felt for her. Every day she put her life at risk for strangers who proclaimed their freedom not to wear a mask and not to get vaccinated was more important than the prevention of a highly infectious disease. Yet when they got sick, they still demanded to be taken care of. I marveled at her persistence to do good against all odds and in contrast my brother’s embrace of hatred.

“You have enough to deal with,” I told her. “Don’t trouble yourself. I hope that you stay healthy and that you find a job that you like more. You can forget about this. You don’t need to do anything.”

* * *

It is the middle of a dark night in 1965. I am awakened by sounds in the hallway outside the bedroom I share with my sister Mimi. Someone is often up at night in our house. It’s been that way for as long as I can remember. Babies wake at night, and I am the oldest in a family of five children. My mother is a light sleeper. It’s usually her footsteps I hear, swishing across the linoleum floor in her slippers, although sometimes it’s Daddy’s heavier tread. If I can, I sleep through it. This night, though, I don’t sleep through it. I hear their footsteps and the sounds of their whispered voices, which are still somehow loud. But I don’t hear what they say. I’m tired, I don’t get up, and soon I fall back asleep.

In the morning, our grandparents are at our house, and our parents and two-year-old Jordan are gone. Our grandparents explained that Jordan ran a high fever in the middle of the night, and our parents took him to the hospital. After breakfast, Grandpa drives Stacy and Lois to kindergarten and Mimi and me to elementary school. Mimi is in fourth grade, and I am in fifth.

We learn that Jordan has spinal meningitis. When they took him to the hospital, he was very sick. But he gets better with treatment, and after a few days, he is well enough to come home from the hospital.

* * *

If Jordan’s spinal meningitis was traumatic for him, he was too young to tell us. But it left its trauma on our mother. She couldn’t forget that Jordan’s illness could have been fatal. If she had not insisted on calling the pediatrician when his temperature spiked, and if the pediatrician had not met them at the hospital, given Jordan a spinal tap to confirm his diagnosis, and administered antibiotics intravenously, Jordan might not have recovered. Mama credited herself with saving his life.

Even being in the room with Jordan while he had the spinal tap was a shock for her. She held him while his back was washed with iodine, and a local anesthetic was injected to numb his lower back. A thin hollow needle was inserted between two lumbar vertebrae, then through the spinal membrane, and into the spinal canal. A small amount of his cerebrospinal fluid was withdrawn and sent to a lab. The presence of bacteria confirmed the diagnosis.

Mama told us that she told Jordan to grip her fingers if it hurt. His two-year-old hands gripped her fingers so hard they left red marks. Afterward, he had a terrible headache, and he threw up.

Jordan recovered from his illness and bore no signs of having been sick. But Mama treated him differently from the rest of us, and she indulged him. Part of it was that he was her only son. But it was also because he had survived what might have been a mortal malady.

* * *

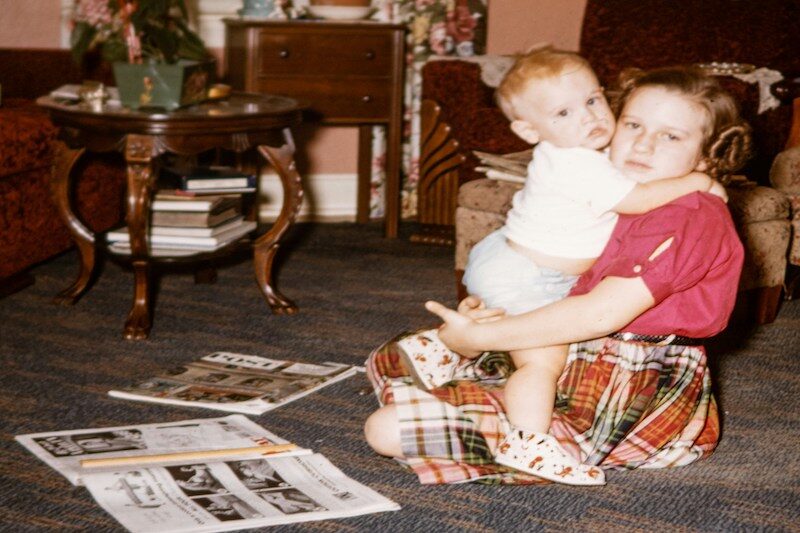

Jordan’s development was more delayed than the rest of us. Mama said it was because he had four older sisters to wait on him, and all he had to do was point and say, “Ugh!” He liked to throw food off the table of his high chair onto the floor and watch us pick it up. Our protests egged him on. He laughed and laughed.

Jordan was born with flat, wide feet. They looked like little clubs. The pediatric orthopedist recommended that he have surgery to form arches in his feet while his bones were still growing. The year after he recovered from spinal meningitis, Jordan had foot surgery. For two months, he wore plaster casts on both legs from mid-foot to shin. When the casts came off, he had indentations of arches in his little feet. He had to relearn how to walk.

From throwing food, Jordan graduated to throwing Grandma’s shoes down the laundry chute into the basement, where the washer and dryer were. When Grandma came over to our house, the first thing she did was take off her low-heeled pumps and pad about in slippers over her stocking feet. Grandma worked in an office all day and wore dresses and skirts. On Saturday mornings, she went to temple. Even on hot days, she put on a girdle and stockings.

When Jordan tossed Grandma’s shoes down the laundry chute, it was more than an inconvenience. In our house, there was no way to get to the basement from inside. We had to go outside and down the front steps and through an exterior door to the basement to retrieve Grandma’s shoes from the laundry basket at the bottom of the chute.

No sooner would we bring them upstairs than Jordan would throw them back down. The more upset Grandma grew, the more delighted Jordan became. This scene would be repeated until we hid the shoes high on a shelf he couldn’t reach.

Another one of Jordan’s favorite pastimes was to throw objects down the toilet—toys, shoes, clothes. He stopped the plumbing up so frequently that it was a running joke with the plumber.

When it came time for Jordan to go to school, he didn’t take to it. The rest of us had to be sick with fever before Mama would keep us home, but not Jordan. Whenever he didn’t want to go to school, Mama gave in to him and let him stay at home, whether or not he was sick.

* * *

There is a fireplace in our living room with a raised hearth set with maroon, brown, and beige ceramic tile. I can’t remember a time a fire was ever lit. My sisters and I use the hearth as a small stage, able to accommodate one person at a time. Mimi and I put on our white imitation Courrèges boots and take turns practicing go-go dancing on the hearth stage. Lois and Stacy copy us, sending us all into peals of laughter. The real hearth of our home is the television set. In the evenings after dinner, we gather around it to watch our favorite programs, its black-and-white glow reflected on our faces.

It is a Thursday night in the spring of 1966, and I am twelve years old. My sisters and I are watching “Bewitched,” about a witch named Samantha who marries Darrin, a mortal man. At his urging, she gives up magic to become a normal suburban housewife. However, her interfering family expresses their disapproval by casting spells on Darrin that wreak havoc with his life. Each episode begins with a crisis caused by a spell. After a series of mishaps, Samantha intervenes with counter-magic to undo the spell and protect her husband.

I sit at the end of the sofa closest to the TV, my social studies textbook on my lap. The sofa is upholstered in a lime-green and brown stripe, and the shag rug is a shade of gold that Mama says doesn’t show dirt. On the shag rug is a bamboo coffee table with a plastic laminate top that resembles marble. Stacy and Lois are sitting next to me, already dressed for bed in their pajamas. Next to the other end of the sofa, in a green armchair, Mimi sits cross-legged, also doing her homework. She is a year younger than I and in the fifth grade. At ages six and five, Stacy and Lois are too young for homework.

During commercial breaks, I read about the history of Mexico in my social studies textbook. Our cocker spaniel Rosie announces her arrival by the tinkling of the metal tags dangling from her collar and the scratching of her toenails against the slippery vinyl tile floor.

“Rosie!”

She lies down on the rug in front of me. Gently I rest my feet on her flank, careful not to burden her. Her fur is soft and warm against the soles of my feet. Against my bare skin, I feel her breath expanding in her body and then contracting.

The show is half over when Jordan comes into the living room in his Superman pajamas, fresh from his bath, his brown hair in a Buster Brown cut damp around his face. He has round brown eyes and chubby cheeks, and he walks with an odd rocking motion because he is still bow-legged from wearing the heavy casts after his foot surgeries.

He sits down right in front of me, crowding Rosie and pushing against her until she stands up and walks away, her tail wagging between her legs. In her place, Jordan parks himself on the rug between my legs, his back resting against the sofa, and takes hold of my feet, one in each hand. He places my feet in his lap.

“Jordan, what are you doing?”

“I want to play with your feet.”

“What?”

“I want to play with your feet,” he repeats.

“Oh, okay.”

He begins by rubbing my feet with his little hands. His touch is damp and a little sticky. I am watching TV, doing my homework, and not paying much attention to him. I barely register when he lifts my left foot in his hand and presses the sole against his cheek. His skin is soft, and I feel his wet lips. Before I can register what he is doing, he is kissing my foot passionately in a way that makes me profoundly uncomfortable. When I wrench my foot away, he protests, resisting me.

I succeed in freeing both of my feet. “Stop it, Jordan! What do you think you’re doing?”

“Please, I want to play with your feet.”

“No, I don’t like it.”

He tries to reach for my feet again, but I tuck them under me, sitting on them so he can’t get to them.

He is crying, begging me.

“I said to stop it! Go away and leave me alone. I’m watching TV.”

But Jordan doesn’t give up. He goes around to each of his sisters in turn, pleading with them to let him “play” with their feet. Over him and around us is the sound of canned laughter coming from the television. One window is open behind me, and a soft spring breeze wafts in, touching my hair. I don’t remember who gave in to Jordan this time. Perhaps it’s Stacy. And then “Bewitched” is over, and it’s bedtime for Stacy, Lois and Jordan.

* * *

In my memory, Jordan’s foot obsession lasted for months. He would come into the living room before bed, while we were watching TV, and beg to “play” with our feet, an activity which involved embracing and kissing them, rocking rhythmically back and forth, passionately and obsessively that we did not understand. Like so much of Jordan’s behavior, we found it puzzling and annoying. We classified it as one of his many oddities.

Looking back after so many years, I still don’t know what to make of what we used to call “Jordan’s foot fetish.” That was our term, without really understanding what a fetish is. Was Jordan’s obsession an innocent manifestation of his childhood sexuality, or a harbinger of more troubling behavior? When I was in college and read Freud, I came to see it as an example of what Freud called children’s “polymorphous perversity.” At the time it seemed to me that something private was being acted out in public. Back then I didn’t know I could have objected to that. Yet, instinctively, I recoiled.

* * *

On another evening of the same year, I was sitting on the sofa in front of the television, already in my robe and pajamas, when Daddy came in the room and sat down beside me, holding me so close, that I could feel his breath in my ear. I try to move away, to give him more room, but he prevents me.

“Let me go,” I squirm in his grasp, twisting my head to get away from his heavy breathing in my ear. At first, I thought he must not realize what he was doing, but when he wouldn’t let me go, I realized that he meant to do this, and I started to tremble. I am on the verge of tears just as Mama comes into the room.

“Let me go.” I implore. “Make Daddy stop,”

Mama is angry at Daddy. “How many times have I told you not to manhandle these girls?” she accuses him.

“I’m not doing anything,” he mutters, as he continues to nuzzle my ear with his cold nose. Though he protests, he lets me go. I run upstairs, not looking back. At the bathroom sink, I wash the feeling of his touch from my ear, but I cannot wash away the memory.

* * *

Ten years have passed: another springtime and Jordan is celebrating his bar mitzvah. Mama and Daddy are hosting the kind of event they said they’d never give. There is a weekend of festivities, beginning with a dinner on Friday night, temple services on Saturday morning, a party on Saturday night, and a final brunch on Sunday morning. Relatives are traveling from near and far. I fly in from New England, where I am in my last year of college, and my boyfriend Keith comes with me.

Every day Jordan receives envelopes in the mail containing checks from people he doesn’t know or barely knows, all because he is having a bar mitzvah. All these gifts are coming to him because he is a boy. In our temple, there are no bat mitzvahs, no equivalent ceremonies for girls. The gifts often include notes from the givers that welcome the opportunity to celebrate our whole family, yet their checks are made out to Jordan.

All of this money and attention focused on Jordan is hard on his sisters, especially Stacy and Lois, who are still in high school. All of us have to work for our spending money. At college, I work at the university art museum and the student health services, and Mimi works in her college library. Stacy and Lois have weekend jobs as hostesses at the Red Lobster. Suddenly, our thirteen-year-old brother had more money than all of us, thousands of dollars, that he did nothing to earn. When Stacy and Lois complain about the unfairness of it, Mama responds with her stock phrase, “Life isn’t fair.”

* * *

Stacy and Lois hoped that Jordan might share even a small amount of his wealth with them, but he did not. To their annoyance, not only did he keep every penny to himself, he lorded it over them. He had always suspected he was special; the bar mitzvah and all the money he got for it was further proof.

On the morning of his bar mitzvah, Jordan was called to the Torah. At that time, our temple practiced a diluted Reform Judaism; there was a choir and an organ but no cantor. The service included responsive reading, a sermon from the rabbi, and very little Hebrew. Even had it been part of our service, there was no one to teach the Torah trope. Jordan was given a few lines of his Torah portion to read aloud in Hebrew and English translation, and the same for his Haftorah.

His Torah portion, from Leviticus, was concerned with sacrifice in the days of the First Temple. When Jordan read the lines, “Take a young bullock without blemish,” his voice cracked.

“Here he is, the young bullock without blemish,” Keith announced that night at the party to general laughter, as Jordan entered the room. Keith’s joke was somehow funnier because of the smattering of pimples across the bridge of Jordan’s nose.

Jordan made a beeline for the refreshment table, where the other boys in his class crowded around the trays of Cokes and chips. Girls in dresses the color of flowers formed their own island at the other end of the table.

A band was playing a top-forties repertoire at high volume. In the middle of the dance floor, my father stood all alone, holding his hand over his good ear. “Where’s Mom?” I asked.

“She couldn’t take it,” he replied. “She’s tired and went home. To tell you the truth”—he gazed around with a look of misery on his face—“this music is like torture to me.”

Keith and I burst out laughing. Dad looked back at us accusingly.

“You can go home, too, Dad, if you don’t like it.”

“I told your mother I’d stay,” he said glumly.

It was hard to hear him over the music. Deliberately, I danced away in a different direction. Colored lights washed the walls, bathing everyone in lavender and acid yellow and sickly green. The band grew louder and more exuberant:

Everybody, get on the floor, let’s dance

Don’t fight the feeling, give yourself a chance

Shake shake shake, shake shake shake

Shake your booty, shake your booty

A strobe sent constellations of light careening across the walls. The pulsing light made the dancers appear to stop and go as if time was constantly resetting itself. At that moment, I didn’t care where I was; I might have been anywhere, as long as I was with Keith. I lifted my face to him and he bent down towards me, and we kissed. I didn’t know if anyone was watching or not, and I hardly cared. I felt something durable with Keith as if he might be a bulwark for me. I felt the two of us might become something together that would last. That he would protect me from my family, and I would be able to bear them better because I didn’t have to share their life anymore. I would not be doomed like they were. They receded from my attention; their troubles melted away. Keith would lead me into a different future, and their concerns would no longer be my concerns.

A shift of attitude can be as simple as a shift of space. This was the fantasy of a moment. I couldn’t leave their troubles behind. Not then, not ever. But with Keith by my side, I was able to view my family through the lens of distance. I could see them as oddities, as separate from me. Being with Keith restored my faith, hope, and sanity. With him, I glimpsed the possibility of a future that was ours, and ours alone.

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

Adrienne Pine

Adrienne Pine's creative nonfiction has been published in The Write Place at the Write Time, Tale of Four Cities, The Yale Journal of Humanities in Medicine, and other venues.