My mom claims that when we were young, she would occasionally go into her bedroom with a book, lock the door behind her and leave my dad in charge of us on those days when, as she said, “I thought I would lose my mind.” I’d often heard my mom say she would Lose Her Mind, but I don’t remember this locked door.

In my memory, she was always around, even if I couldn’t see her.

My dad left her each morning with a kiss and three kids at the breakfast table. She handed us our lunch bags on our way to catch the bus, and was there when we came home. She was like the basement furnace. We didn’t notice it churning away behind the closet door, but we would have known if it shut down. Any time we needed something, we could seek her out in any room in our house, including what should have been the privacy of her bedroom.

Through the open door, the king-size bed floated above the blue carpet like an anchored ship. If one of us had a nightmare, she folded back her sheets and let us crawl in. On school nights, we sat on the floor with our backs against it and watched The Monkeys while she read The Ladies Home Journal. Sunday mornings we sprawled out on the bed in our pajamas while she and my dad reclined against the pillows and read the newspaper. We fought over the comics, scratched the dog’s belly and pestered our mom to get up and make us breakfast. She would eventually sigh and fold the newspaper, zip a bathrobe over her silk nightgown, and march down the hall to the kitchen, her pink scuffs slapping behind her.

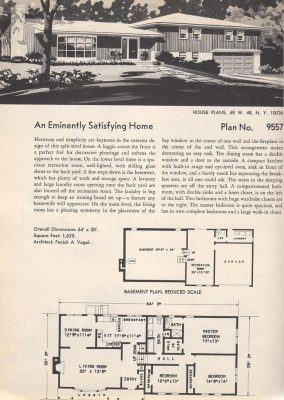

Our house was cutting edge when we moved into it in 1964, a custom design for the modern family seeking space and stability in one of the new neighborhoods sprouting in fallow wheat fields outside the city. The developer had bought a rural farm on a wooded hillside, erected a brick entrance sign with “Forest Hills” emblazoned in cursive print, and built a rapid succession of family homes on three tiered streets. Most of the houses followed the split-level, bi-level and raised ranch designs recommended for young families.

Family experts from pediatricians to psychologists believed children should have independent spaces for healthy exploration within the protective shell of house and yard.

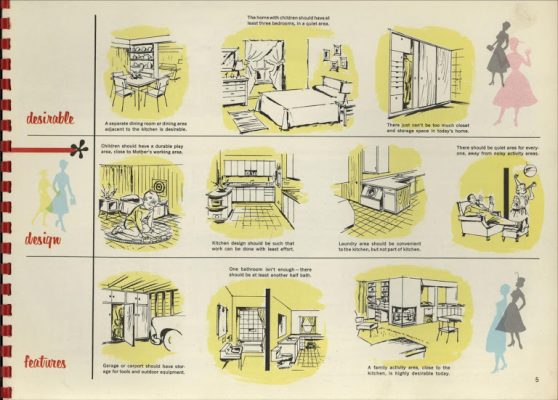

In 1956, The Housing and Home Finance Agency gathered 103 women from across the nation “to obtain the ideas of American housewives on home planning and design.”

The Women’s Congress on Housing list of suggestions mainly centered on one thing: space.

“More space–space for things, space for people, space for escape.”

They wanted informal spaces for the noisy activities of children, hidden spaces for laundry and bedrooms, and formal spaces for guests and “gracious living.” As one woman argued, “parents are valuable, important people. Fewer would go to our mental wards and divorce courts if they had one room, even a small one, just for themselves…”

Some builders scoffed at their list and proclaimed it cost-prohibitive, but architects found a way to fulfill it affordably. The split-level design divided public and private spaces by short flights of stairs rather than walls and doors. The design was also cost-effective for the small sloped lots like Forest Hills. Constructing the basement on the slope eliminated the cost of a full excavation, brought in more natural light, and created division without complete separation.

The developer of Forest Hills was also a custom builder. So our house was actually a combination of several designs he tweaked to create a perfect balance of open space and private retreats. Home plan catalogs like Distinguished Homes for Modern Living and Home Designs for Luxurious Living offered varying configurations of split-levels, bi-levels and raised ranches designed with the modern housewife in mind.

The National Plan Service catalogs urged women to “plan your new home to be a perfect fit for your family….let it fit your family’s needs…your personal tastes…your desire for individuality…your ideas of style….”

Our custom-designed split-level/raised ranch home was nearly everything The Women’s Congress of Housing desired.

The design may have been ideal for the Women’s Congress, but it was an ill fit for my mom.

When she married my dad in 1952, she was twenty-one years old and living in two-bedroom shipyard slum house. She and her two brothers spent much of their childhood fending for themselves while avoiding their alcoholic father. Their house was a precarious place whose tiny dimensions trapped them in turmoil from which their fearful mother couldn’t shield them. So my mom gave us grassy yards instead of dirt streets, toy-filled Christmases without drunken fights, and rooms with doors we could shut to escape the inherent chaos of family life.

But privacy in a split-level was as insubstantial as the pocket doors separating our kitchen from the living room. Our house had a built-in intercom system to help my mom with supervision, but it was unnecessary. The split-level may have claimed a proper amount of division, but sound suppression was nonexistent. Pretending the functions of a house could be separated into formal and informal spaces was as unrealistic as believing every woman could be fulfilled as a mother.

The design of the house was deceiving.

Visitors entered the glass-flanked front door and walked into a white-tiled entry with a soaring ceiling topped by a brass chandelier. It was a small, elegant space at the home’s crossroads, offering visitors a view of cool serenity. The door was designed, so visitors instinctively walked up the stairs on the left rather than walk down the stairs on the right, so they were greeted with the pristine luxury of the Living Room rather than the chaotic workings of The Family Room.

Distinguished Homes for Modern Living Plan 560 advertised the space as an “extra special plan for families with lively youngsters…it takes care of practically all their needs and spares the rest of the house.”

With its paneled walls, brick fireplace, and furniture facing the T.V. in the corner, everything in this room was multi-purpose. When we had overnight guests, my mom unfolded the hide-a-bed. For birthday parties, she pushed the furniture against the wall and set up folding tables and chairs. My mom’s ironing board and sewing machine allowed her to work while watching T.V. It was a room for forts and slumber parties and Friday nights with The Brady Bunch and Partridge Family.

Next to the Family Room was the Playroom where the furnace churned away behind one closet while another held Barbie Dream Houses, Hot Wheel tracks, and Childcraft Encyclopedias. Without furniture, lamps or pictures on the walls, the room could withstand a lot of noise and motion and squabbles, or as much as my mom could take. Upstairs in the kitchen, her shoulders and neck responded to noise levels like an equalizer, and when the bar went into the red zone, she hollered a warning at us over the stairwell.

The split-level kitchen provided a direct conduit to every room in the house.

Plan 560 was designed so “mother in the kitchen can keep in touch with activities in the play yard, just outside, or the family room, just four steps down.” Our split-foyer added ten more steps for a bit more separation, but it still wasn’t enough for my mom. While she read her Better Homes and Gardens cookbook and struggled to put dinner together, she could hear slamming doors and pounding feet running up and down the stairs as three children battled for supremacy. She followed the recipe for Ground Beef and Rice Meatballs accompanied by the canned laughter from Gilligan’s Island, my sister banging out scales on the piano, Hot Wheels cars colliding on the tracks. After dinner, we headed out the back door where my mom monitored our activities from the window over the sink. And if we ventured down the line of backyards to a neighboring house, she could step out the back door and blow my dad’s referee whistle to signal us home.

The split-level design, however, also provided areas of beauty and calm where mothers would not Lose Their Minds.

My mom decorated the living room with Lane Danish Modern end tables, a sofa and two chairs of burnt orange nylon. Beige shag carpet softened the floor, tall wooden lamps with flared bases flanked the sofa, and the fireplace stone hearth held a brass tool set and an abstract wood sculpture of Picasso-like musicians. Her artwork included a mix of contemporary Still-lifes on the wall and sculptures of glued jars covered in gold-painted aluminum foil she made in a class called “Handicrafts for the Home.”

Home Designs for Luxurious Living Plan 571 was sure “the separate dining area will warm many a housewife’s, heart.”

Because it was reserved for company and family dinners, she furnished it with a polished walnut dining room set and high-backed chairs always at ready attention. My mom hadn’t grown up with style, but through The Ladies Home Journal and furniture showrooms, she cultivated one that seemed to blend the simplicity of Scandinavian Wood with a splash of Psychedelic Pop.

She extended this personal style to The Master Bedroom, the part of the modern home meant to be a luxurious and private refuge from family life. Distinguished Home Designs for Modern Living Plan 719 proclaimed “the master suite is the ultimate in living luxury…privacy is completely assured.”

This was where my mom could refresh and reinvigorate the part of her depleted by children. And my mom tried to make it so. She decorated it with the same care as the living room, with dark mahogany dressers and nightstands, a bench upholstered in the same pale blue crushed velvet as the bedspread, and a round swivel chair for quiet reading.

When the king-size bed was made, and the floor-length curtains opened, the room took on the fine elegance of a china plate. And a true Master Bedroom had an attached Master Bath for the ultimate in privacy and luxury. Even when the bathroom was still filled with steam from her shower, she had already wiped the white-tiled counters clean and hung fresh towels on the brass towel bar. Her Estee Lauder makeups and lotions, nail polishes and emery boards, were all corralled neatly in the vanity’s drawers.

It was clean and serene, but hardly a retreat.

The Master Bedroom was even more centrally located than the kitchen. It was only six steps down the hall from the kitchen and two steps across the hall from our bedrooms. It was directly over the garage with a picture window facing the driveway and street. When an occasional car accidentally drove down our street and turned around at the dead end, mom Watched it Like a Hawk. We were the last house on the block, so the only cars parked at the steel barrier were Up to No Good. Mom peered out this window, eyeing the cars, memorizing the details in case she needed to make a police report. As we became teenagers, she began eyeing every car we drove away in, whether it was a parent or a friend, until we disappeared from view.

Her silhouette at the window was always the last thing I saw when I left and often the first thing I saw when I returned. Even if she was already in bed, I couldn’t tiptoe past the room without her stirring and sitting up and asking what time it was. Mom presided over The Master Bedroom like a prison guard or safety net, depending on our age and level of independence. Whatever it was, there was no getting past it. So we invaded Mom’s Master Bedroom and took what we needed, whether it was clothes, makeup, or her privacy.

Mom cleaned the house every Saturday, sometimes adding a Lick And a Promise cleaning in between. My Chore Board job was dusting. I slapped away at the furniture, skirting around tabletop items until I got to her bedroom.

With the vacuum humming downstairs, I rifled through her lingerie drawer to sniff the wrapped bar of soap she kept underneath her bras. I opened green brocade boxes of tightly rolled nylons, silk scarves and white handkerchiefs, their corners embroidered with delicate flowers. I opened her jewelry box and tried on the gaudy pieces she never wore, wrapping jewel-encrusted bracelets on my thin arms, clipping on rhinestone earrings and draping thick, tarnished chains over my neck. I walked into the closet and brushed my hands against racks of skirts and slacks. The top shelf held her purses, and I rummaged through them until I found a roll of Pep-o-mint Lifesavers. In the bathroom, I opened her box of scented powder and patted the fluffy pouf against my neck to see the powder rise up like a perfumed prairie wind.

If I heard my mom coming down the hall, I scurried back out of her room like a thief. Although her bedroom wasn’t off-limits, I was pretty sure the contents of her drawers were. My mom’s bedroom was an inner world as mysterious to me as the round compacts of little pills labeled with the days of the week, the blue boxes with paper tubes lined up like cigarettes.

On the rare nights she and my dad went out, I sat in the bedroom chair and watched her change. The room was dim with evening lights as she studied her closet and pulled out different combination of skirts and blouses and laid them on the bed. She took a pair of nylons out of their brocade compartment, eased them over her feet and rolled them up her legs.

I listened to the sounds of glass jars and enamel cases clicking open and shut in the bathroom, heard the brush teasing and plumping her softly-styled blonde hair as she patted it into place with Adorn hairspray. She smoothed her skirt in front of the full-length mirror, eased her feet into cream high-heeled pumps, and selected a small black purse with a gold chain for a strap. When she took my dad’s arm and walked out the door, she left behind the scent of Chanel No. 5 in the foyer.

In the morning, we crawled into the king-size bed to watch cartoons while they read the newspaper with bleary eyes. We sniffed the air like dogs, curious about the strange smells they brought home with them. Stale smoke and grilled food, a hint of alcohol, and my mom’s perfume and powder scented the room as she shook out the newspaper and tried to ignore us.

A team of experts and builders and 103 housewives custom-designed a home for the mother of the 60s, but it was a poor fit for my mom.

We devoured her space and mind because she didn’t know there was any other way for a woman to live.

Photo from the Archives of the National Plan Service Modern Living Fashion In Homes

Darcy Lohmiller

Darcy Lohmiller is a middle school librarian in Bozeman, Montana. Her essays about fishing, hunting, dogs, and trailers have appeared in The Drake, The Flyfish Journal, Shooting Sportsman Magazine, and The Big Sky Journal. You can read her essays at https://www.clippings.me/dlohmiller

Darcy,

Your well-researched story brought back so many memories for me growing up in a post-WWII planned subdivision I loved your copies of the ads listing all of the features for the “modern” family. Watching my mother get ready for Saturday night dates with my father both enthralled me and made me wish my grown up life would hurry up and start. Although my grown up life ended up being nothing like my mother’s in our Stepford neighborhood. My mom was one of the few mothers who worked outside of the home and introduced the first wave of feminism to me. Her escape was not the master bedroom, but the verboten world of work I absolutely ad0red your blog–it was like opening a time capsule for me! –D.